Portland Metrozine |

| Sonorous Waves |

By Mehreen Ahmed |

| Archeology |

By Shavaun Scott |

| The Executioner’s Wife |

By Mark Kodama |

| Suite of Poems |

By Michael Lee Johnson |

| Big Red |

By Andréa Montoya |

| Three Poems |

By Angie Ebba |

| Gallery Walk |

By Fabrice Poussin |

| Blood and Bones |

By Dawn Tyree |

| Quartet of Poetic Forms |

By Mary Ellen Gambutti |

| Beyond the Suburb & Loggerhead |

By Kenneth Pobo |

| Slice of Life |

By Prisoner # 53.3.8.5.7 |

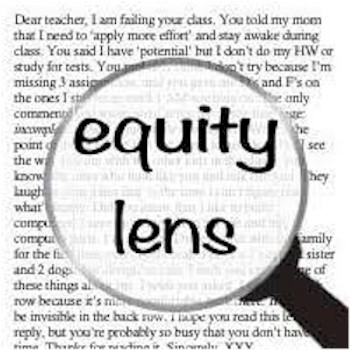

| Spotlight On: Refracting My Equity Lens |

By Basha Krasnoff |

| Remembrances |

We share our gratitude for the loving and inspiring mothers who blessed our lives through their everyday words and deeds. |

Blossoms falling

|

|

| Flash Fiction |

Sonorous Waves By Mehreen Ahmed Two helicopters flew over our heads, like a duo dragonfly in the autumn sky. This afternoon, my sister and I sat under an old, oak tree in our garden by the River Bhairab. Those were the days, when we chatted silly, and talked about every nonsense that entered our heads, giggling over nothing. “Let me guess, you don’t like that. This life of the mind kind o’ thing,” I laughed. “You know how it is, thinking, dreaming.” I laughed first, then she laughed with me. I hadn’t actually realised it until now that she mentioned it. Yes, I was the more reflective one; she, the extroverted. But that was all the difference we had; we both stood on a common ground of compassion. Well-bonded in togetherness. When we were growing up, much of the political discussions in our house centred around the partition of India. Discussions which shaped our world views, so much so that it made us opinionated. We always heard about these eternal qualms between the Hindus and the Muslims. The Hindus suffered in the hands of Muslims at partition, and now it was the Muslims' turn to suffer in the hands of the Hindus. The power shifts, after the British had left. The crooked history never left us at peace, not today, not ever; if any, it made us even more crooked, hating everyone, in our loveless lives. These clockwise and anti-clock motions of emotions ran hot and cold, politics played and churned out generations of despicable events. Dramas that we saw around our kitchen table bore that testament. Our parents endlessly bickered over what should have been the right course. Disagreements, led to high levels of anger, at times, shouts grew louder, arguments deepened. We listened and left the table when we couldn’t endure anymore. We started living in a distorted reality of ideas. I looked up at the sky, such a serene afternoon, today. At the far end of the garden, our Gardener, weeding nettled locks from a thorny rose tree. He looked at us and nodded a greeting with a smile. We smiled back. The garden looked deliciously luxuriant or decadent, this time of the year. It burst into all sorts of nature’s vibrancy, as the colours of spring changed to warm scarlet, deep magenta, sea turtle emerald and saffron pouring onto our lawn. Impeccable, was the word that summed it up. However, the Gardener’s intrepid work at cleaning the fallen, decrepit leaves, could not be ignored. It was his job to bring the garden to a full bloom every spring, of roses, and white jasmine, and pink daisies, and his job as well to clean it all up throughout autumn. Yes, pink daisies, the most prolific of all, the Nordic goddess, Freya’s sacred colour, symbolising, love, beauty and fertility. “It is beautiful, wouldn’t you agree?” I asked my sister. She looked at the garden, then at the Gardener, and then his broken hut by the river. And nodded in agreement. “Do you think, he is in love?” she asked. “Maybe, we never really speak to him, do we?” I said. “Hmm. I wonder sometimes.” “We do speculate a lot,” I laughed. She laughed with me. The Gardener overheard. The tinkle and the words carried over by the autumnal air. “Should we ask him?” asked my feisty sister. “About what? If he is in love?” I asked in disbelief. “Yes, if he can create this lush place of such breathing, blooming flowers, he must have a heart, too; sensitive enough to love and to kiss.” The Gardener, in my thoughts, swam in the deep river, and then suddenly, he kissed a girl there, in the river’s depth, a secret he harboured. He summersaulted in the water and swam away. “Yes, I do realise. Do you think, life would be any less miserable with the Gardner than it is right now? To the contrary, life may actually flourish.” We both looked at his hut. And thought how the rainwater never affected him. Then there was a cry. It came from the Gardner. We rushed towards him. He had cut off his index finger, and then tried to re-attach it. Red blood oozed out on the manicured lawn. A snake had bitten him, a brown, poisonous viper. It slithered away right before us. “Oh! No!” We screamed. “You must go to the surgery at once. “It’s okay. I’ll go to my hut and rest. I’ll be fine tomorrow.” “But you’ve lost so much blood.” We heard the sonorous river convey, Roof’s torn portal led to spacetime above;

|

|

|

| Poetry |

Archeology By Shavaun Scott It’s 3 am and the world is holding its breath I sit alone in moonlight and shadow storing artifacts of regret out of reach, a night bird pauses in its hunt the stealthy black cat prowls in the yard below darkness covers dried bones, but don’t worry the breeze carries sandalwood and night jasmine clouds cross the moonscape

the stars are a distant campfire it’s not what you think it is, it never is, I cry out in another tongue It’s 3 am and the world is holding its breath

|

|

|

| Historical Fiction |

The Executioner’s Wife By Mark Kodama

I. Yesenia At a conference on human rights at the Hague, I met an activist, a quiet unassuming middle-aged European-looking woman who spoke English with a barely noticeable Spanish accent. She was a clean, thin, well-mannered woman, almost timid. Her perfume was understated. But when she spoke her eyes became lit with fire and she spoke with power. Her name was Yesenia. This is her story.

“When you hear about Central American dictatorships, kidnappings, tortures and murders, I know they are true,” Yesenia said. “I was the executioner’s wife. I can still see the ghosts of the disappeared. Their faces haunt me still.” “I come from the land of the trees. It is a magical land with high mountains, great volcanoes, Mayan ruins and all kinds of plants and animals. We have two great oceans. Some say the land is so fertile because of the volcanoes. Others say it has been watered by the blood of martyrs. We have coffee, bananas, cotton, sugar cane, avocados and the world’s largest carrots. We have great Mayan ruins, great Spanish colonial cities, painted in the most colorful pastels, old Spanish cathedrals and churches and one of the new world’s first universities. We have three UNESCO sites. “More than sixteen million people from all over the world live in our country, the most populous in Central America. But the majority of people are Indianos, descendents of the ancient Mayans. Many still dress in hand woven colorful clothes of their ancestors – black, lavender, blue, red, pink, y verde. In Guatemala, you can meet someone and they will be your friend the same day. Truly the people love their neighbors and God with all their hearts. “And the food? Muy delicioso. Chocolate, coffee, tacos, fish, chicken, beef, guacamole, corn soup, fruit drinks and chuchitos. Ever had fresh goat’s milk? They sell it on the street of Guatemala City. “I grew up on my father’s estate outside the city of Antigua, one of three UNESCO sites in my country. I attended an all-girls private Catholic school and church on Sunday. “My favorite teacher was Sister Maria. She taught religion and philosophy and literature. One day, the boys’ team was practicing penalty kicks on the football field. Sister Maria asked the boys if she could try to shoot a goal. She removed her shoes. From the time she picked up the ball, turned it and then placed it on the ground, you knew she knew. She appeared to kick the ball to the right of the goalie only to change directions and let loose a rocket to the goalie’s left. After class that day I asked Sister Maria if women really came from a man’s rib. She smiled and said ‘Someday, child you must decide this question for yourself.’ “One day, a Mayan girl joined our school. All the girls but me made fun of her dress, lack of sophistication, and imperfect Spanish. Sister Maria, furious, castigated us. ‘Who do you think you are,’ she asked us, her brown eyes bearing down upon us. After she finished, we were silent. She looked at me and said ‘Evil flourishes when good people do nothing.’ “My father was a military man – a general. We were from a landowning family. He was an ardent anti-communist. As the patriarch of our family, his word was law. “My husband Juan Carlos was from a civilian family, the son of the owner of a trucking company. He was a dashing young intelligence officer with great promise. “My father was European, a Spaniard, the descendent of a Hidalgo family, who had come to Mexico. Juan Carlos was a Mestizo. He was a quick and decisive man. He was medium height but built like a bull. He was tough. My father loved him - I think more than me. “It was a grand wedding. Sister Maria wished me the best of luck. My father was so proud. My mother wept. “I was young and beautiful then,” Yesenia said. She paused and said, “Now, look at me.” She laughed in a sad way. The waiter brought in a glass of ice water. She thanked him. She showed me a black and white picture of herself when she was twenty. She was beautiful. “I taught Sunday school and religion for Sister Maria at the school. We often hiked in the surrounding hills with the students. Sister Maria led the way with her hand-carved walking stick. “Meantime, Juan Carlos rose through the ranks. Col. Armas led his military force and brought down the Arbenz government. My father repeatedly warned President Arbenz he was moving too fast and it was folly to challenge the United Fruit Company and the Americans. President Arbenz said he was only buying uncultivated land for the people at the value declared by United Fruit. “Afterwards, followers of Arbenz and suspected communists and dissidents were rounded up, imprisoned and killed. But rather than end the unrest, it only seemed to accelerate the divisions in our society. During this period, Juan Carlos became busy, receiving several promotions. “Then a curious thing happened. We went to a party. Everyone feared us. Friends of mine asked me to ask my husband the whereabouts of their loved ones. II. Commander Zero “We left early in the morning with our driver Pablo, driving through the narrow cobblestone streets of Antigua and on the highway to the mountains. I know I am prejudiced but I think my country is blessed with the most beautiful mountains in todo al mundo. “We were soon on a dirt road with green jungle on either side of us. We soon came to an abandoned village. We parked the truck and carried food and milk in backpacks into the mountains. We soon came to caves the entrances enclosed with mud brick walls. “Little hands reached out from the caves. ‘Milk, please, milk. We are hungry,’ called these little voices. Sister Maria took off her backpack and smiled. She reached in and gave bottles of milk to the little outstretched hands. “We’d often visit people living in the mountains and in the jungle, delivering food to starving children. Meantime, the violence continued. The newspapers reported that rebels attacked government forces and civilians. “Sometimes, Sister Maria led us into the mountains. Other times, I led groups into the mountains. It was during a trip I led that we first encountered the guerillas. “Pablo was driving the church pick-up truck down a narrow dirt road through the jungle when we came to a meadow. Five rebels in uniform armed with Soviet-made rifles stopped us. The commander, wearing a black beret and chewing a cigar butt, approached Pablo. He was a young man in his mid 20s. He had a scruffy beard and wild uncombed hair. His army shirt hung outside his pants. He motioned us to stop and then told us to get out of the truck. “Who is in charge here?’ he asked.” “I am,” I said. “No, stop,” I said. “These are not for you.” He looked surprised. Then he said coldly: “Yes, but they are now.” “These are for the children,” I said. He then pointed his gun at me. “Stop,” I said again. “We don’t want trouble. We just want to help the children.” He lowered his gun. “Who sent you here?” he asked. “The church,” I said. “He nodded. He then told his men to stop unloading the truck. He and two of his men then climbed into the bed of the truck. “He then smiled and said: 'Well, what are we waiting for. Let’s go.' He banged the roof of the cab with the flat of his hand and pointed forward with his gun. “When we arrived at the village, everyone seemed to know the commander. He and the second man then helped us unload the truck. He was average height but strong. The children followed him with quince wood rod sticks they used as rifles and small sticks in their mouths, their cigar butts. He saluted the children. They saluted back. “After he unloaded the truck, he thanked us and then he and his men slung their rifles over their shoulders and disappeared into the jungle. “’Who was that?’ I asked the mayor of the village.” “’That was Commander Zero,’ he said.” “About a week later, I read in the paper that a government patrol had been ambushed in the mountains by Commander Zero. “Whenever, we delivered food in that part of the country, we often encountered Commander Zero who escorted us to our destination and then helped us unload our truck. “One time, I asked Commander Zero why he attacked and killed soldiers who were only trying to protect our country. “Commander Zero looked at me with a glint in his eye and said: ‘Senora, I am like Robin Hood. I borrow from the rich and then give to the poor.’ He then laughed. “’We only fight the soldiers and police who oppress the people,’ he said.” “Then why do you bomb the people?” I asked. “’That is a lie,' he said. 'We only fight the soldiers and police. We give no quarter and expect no quarter. We do not harm the people. And if we capture soldiers, they are treated as prisoners. We represent and fight for the people. For this cause, we are prepared to give everything, including our lives.' He then looked at me earnestly and asked: ‘Do you really want to know why we are fighting the government?’ “I said: ‘Yes.’ “‘Then are you prepared to hear true stories not reported in the newspaper?’ he asked. “Yes, if they are true,” I said. “‘Then come with me,’ he said. “He took us blindfolded to his mountain camp. He introduced us to one young woman guerilla named Hilda. He asked her why she joined the rebels. “‘The Army came late at night,’ she began. ‘After they climbed over our front wall, they broke into our house. They shot my father and then tortured my mother in front of us. They pulled out her finger nails with pliers. They put a sack over her head and took her away in a car. We never saw her again.’ “He then introduced us to a thin man in his 50s. “‘The Army arrived at our farming village at 5 a.m.,’ the man said. ‘They took all the men and boys of the village to the church. A hooded man picked out certain men and boys. The soldiers took them to the school. “’The soldiers then marched us to the cemetery and ordered us to dig a large pit. As we dug, shots rang out. As we finished digging, they brought the bodies of twelve of our neighbors and threw them into the pit. They ordered us to bury them, some were still moving.’” III. Juan Carlos “That night, I asked my husband Juan Carlos what he really did for the military. “’I fight Communistas and terroristas,’ he told me. I felt a chill sweep through me. His eyes became dark like a wolf. After that I could no longer sleep with him. It was fine with him for he had a young mistress and child he kept in Guatemala City. “Meantime, more of my friends asked me to ask Juan Carlos to intercede for them or provide information as to some loved one. Juan Carlos just nodded. He began to drink heavily. “He was afterward promoted to colonel. “That night Juan Carlos said they were kidnapped by rebels a week ago but did not know what happened to them.” “The next time I saw Commander Zero, I asked him if he knew their whereabouts. Commander Zero said they were taken by the soldiers. “You are a liar,” I told him. “’Senora, I tell you the truth,’ he said. ‘It happened here in this village. If you do not believe me ask friends here you trust. They like you. If you ask them discretely, they will tell you.’” I did. “The people said the soldiers took them. The mayor gave me Sister Maria’s walking stick. “I did not mean to fall in love with Commander Zero. It just happened. “Commander Zero was not Guatemalan. He was from a good Argentinean family. He was well read and studied architecture like Che Guevara who was his idol. Commander Zero was an intellectual and a man of action. He spoke of liberating the poor of Latin America from the Yankee capitalists and the dictators that they supported. Our leaders and military do not support the people but the Americans and themselves and their own selfish interests. “’We must win the support of the people,’” he said. “‘Without the support of the people we are not revolutionaries but mere bandits. “’Revolution must start in the rural areas,’ he preached. ‘The government is too strong in the cities. But we in the countryside we have the advantage: knowledge of the terrain and support of the locals.’” “One time, he took me to one of his ambushes. We waited until night fell. He divided his forces into two. When the government came through the pass, his men began shooting the soldiers in front, dropping the two lead soldiers. Commander Zero was everywhere: leading the attack and then covering the retreat, seemingly oblivious to the enemy gunfire. As the soldiers began to attack, the second force opened fire from the left side. Three more soldiers fell. The rebels then all retreated into the jungle. No one was injured. “We soon became lovers. One night when we were together, army helicopters descended upon the village. A great shootout followed and a half-dozen died on both sides. Commander Zero and his men fled into the jungle. I prayed I would see him one more time. I came to regret that prayer. “Afterward, there was a great manhunt for the rebels. The newspapers reported several battles with dozens of dead on both sides. “One afternoon, Juan Carlos asked me to come to see him at the police station. He was in an interrogation room. He asked everyone to leave. He was sitting in an old dark wood chair at a long wood interrogation table. A hat box sat on the table in front of him. “When he opened the hatbox, the head of Commander Zero stared at me.”

|

|

|

||||

| Poetry | ||||

Suite of Poems By Michael Lee Johnson

Dance of Tears, Chief Nobody (v5) By Michael Lee Johnson I’m old Indian chief story I feel white man’s presence I’m Blackfoot proud, mountain Chief. I roam southern Alberta, Now 94, I prepare myself an ancient pilgrimage, I walk through this death baby steps, I’m old man slow dying, Chief Nobody. An empty bottle of fire-water whiskey

Missing Feeding of the Birds (v3) By Michael Lee Johnson Keeping my daily journal diary short These few survivors huddle in scruffy bushes. I drink dated milk, distraught rehearse nightmares of childhood. I feel weak and Jesus poor, starving, I can’t feed the birds. Guilt I cover my thoughts of empty shell spotted snow

Open Eyes Laid Back By Michael Lee Johnson Open eyes, black-eyed peas,

Tequila (v5) By Michael Lee Johnson Single life is Tequila with a slice of lime,

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

|

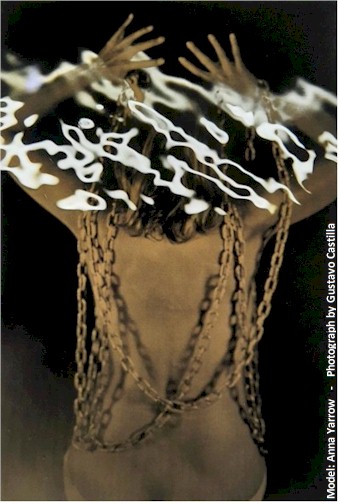

| Metrozine Gallery |

Gallery Walk By Fabrice Poussin |

|

|

| Poetry |

Quartet of Poetic Forms

She Couldn't Say Haibun By Mary Ellen Gambutti "Remember, she couldn't answer your questions without revealing everything. If you hadn't searched for her she would have taken all her secrets to the grave." Your words stung. Our only chance the year before she vanished—in and out of our lives. Could I be grateful for all that came of it? The rarity of our meeting? Mute about my father--maybe she strained to remember—the truth ever elusive. Her life of neglect and desperation well known to you; abandoned as a toddler to her own poor parents’ shack. And I—longing for my own truth—flew to you both. Sister, you suspected there were others, but she couldn't say. worn wooden bench—

Happenstance Prose Poem By Mary Ellen Gambutti Was there intention in Virgo? Carolina’s cloud-masked stars glimmered weakly on my origins. September birthdays brought sweaters and school-time, parties postponed by a typhoon’s tempest and Texas hurricane. Storms and swoons of uncertainty. The profanity of accident. Prophecy of place and time. Meant to be--raison d’etre--the designated date, my unjoyful occurrence. Unloved Leila, left alone. Always lonely. Abandoned—first she, then I. Could she, on rising from her birthing bed, consider beyond surrender, that facts would be muddled, muddied? That papers given my fosterers would be fabricated, a flimsy truth? That in a mystery hour, no tiny feet impressed? Schoolmates knew their truths. I burned to tell some uncertain story, and had only abstractions. Only, it happened! My birth happened. This is my story, I told them: “Not this mother, but another mother.” I couldn’t tell them what he told me. “She died,” he said, “in a car,” with others, maybe girls and boys, maybe a man who would be my father. A family died. He must have lied; adopted dad. “They’re gone,” he said. He must have meant to console: “You have us.” I tell them on the playground, “I’m adopted.” That’s good, we all decide. Because I have parents. People take care of me. I’m different; a mystery. Mystified. I learn a story that came from out of the blue, blue like a September sky, like this sapphire birthstone worn on my seventh birthday, soon lost.

Remembering Agnes Remembering Zuihitsu By Mary Ellen Gambutti Agnes, my mother, turned ninety-six this August. The elder of her two adopted daughters, it’s fallen to me to keep connected with her and the nursing home staff in Pennsylvania. I’m fine with this obligation to the only mother I’ve ever known. Sedoka a role model for impatience never a good listener, "Don’t forget to call me!”

|

|

|

| Flash Fiction |

Beyond the Suburb By Kenneth Pobo I first watched it when I was a high school sophomore, home with the flu, feeling better but still weak. Mom put a silver pail down by the couch “in case you need to puke, use this.” I did need to puke when I got up, but that was hours before. She grabbed the pail and flushed the puke. She sat in the dining room in her usual chair under the cuckoo clock with the annoying red bird that popped out, and read her Devotions. She tried taking me to church many times, but it didn’t take. The film was called Beyond the Forest from 1949. I hadn’t come out myself yet. I got together with Tom Konwitz for what he called “fun.” It was fun. I looked forward to those times. He said, “It’s just something to do.” Bette Davis, wearing a strange black fright wig, was Rosa Moline: “a twelve o’clock girl in a nine o’clock town.” Drab as a fence post husband Joseph Cotton, oh so very good, oh so unappreciated—in a town no one wants to visit. Bette plotted to escape. Maybe a rich Chicago dude would make her rich, offer her the gift of excitement. Other than my romps with Tom, not much got exciting in Gradyville. Philadelphia was fairly nearby, but I didn’t take the train in much. My dad said, “You’re such a scatterbrain, you’ll lose your wallet, and I’ll have to come get you, and you know I won’t be happy about that.” That dullard friend of her achingly good Cotton, Moose, who she, oops, kills, said, “You’re one for the birds, Rosa, one for the birds.” I, too, was for the birds. I waited for bluebirds to return in spring, hung a picture of a snowy owl on my bedroom wall. It looked like Peggy Lee. Of course, I got better and high school roped me back in and covered me in geometry. I had gotten beyond the suburb. I didn’t want a saccharine doctor to house me or a small town or suburb to keep me in one form of high school after another. I knew I’d leave. Mom’s cuckoo clock bird kept returning to the clock’s innards. Maybe it would be a city. Maybe not. My time to fly kept getting closer.

|

| Flash Fiction |

Loggerheads By Kenneth Pobo Raylene sees her mother as a parking meter taking quarters but providing no time. They fight and don’t talk for days. Her mother watches sitcoms because by 8:25 p.m. everyone hugs. Raylene prefers detective shows: the crime like a joke, she tries to guess the punchline. She wishes that she and her mother could share a sniff of a Tropicana rose by the back door. The bush won’t survive a bad winter. |

|

|

| Creative Nonfiction Vignette |

Slice of Life: Freedom in the Moment By Prisoner #53.3.8.5.7

Suddenly, to think that I may actually be here seems completely insane. In moments like this it feels like I am living the life of " Andy Dufresne” or "Ellis ‘Red’ Redding", not my own. In this moment I think of the stark contrast of my life before compared to the life I live now. What would I be doing now? I wonder. I glance at my watch. Eight thirty-seven on a Sunday morning. Well I'd be in sweatpants getting coffee, I think with certainty, sweatpants, coffee, and heading to the beach on this undoubtedly shitty, wonderful day there. My thoughts drift again as I step on the track. This is part one of my New Year’s resolution. Part two is no sweets and no more freaking ramen. I chuckle as I put on headphones and turn on my radio. I get two steps before it shuts off. I press the power button. Two feet. Off. Lifting the radio up I can see the screen flashing " LOW BATTERY" in an aggressive, wasteful way that could probably be used to listen to music. "Fuhck," I mumble, "Typical." Shoving the radio in my pocket, I leave my headphones on to ward off anyone who might want to talk to me. The brisk air is pleasantly refreshing and with a bit of child-like amusement I drag and kick my feet through the thin layer of snow that covers the ground. One mile, two miles, three. Tuning out from the world, I give it rapt attention. The rising sun slowly burns away cloud cover to reveal a wintery pale blue sky, the contrasts of sun and snow is both blinding and beautiful. Looking past razor wired fences at the row of squat, snowcapped mountains lining the horizon, I think longingly about how just a piece of gum would be pretty fine about now. Four miles, five miles, six. Then, the sound of someone deep throating the microphone to the PA system. A sound I recognize as "yard in". ▀ ▀ ▀ |

|

|

| From the Editor's Desk |

Spotlight On: Refracting My Equity Lens Many of us would agree that personal economic, social, and political outcomes should not be predetermined by an individual’s race or gender or economic status or sexual orientation or physical ability. We agree that the qualities of justness, fairness, impartiality and even-handedness are the goals of equity. Whereas equality is all about equal sharing and exact division, equity levels the playing field to ensure that any person’s starting line does not automatically determine where that individual finishes. What I have grappled with and have not quite grasped, however, is the notion that I can apply an “equity lens” in my approach to life and somehow see the world outside the confines of my own racial/ethnic/gender/sexual orientation/physical ability perspective. In this “brave new world,” I find myself consistently confronted with “blatant injustices,” "alternative facts," and “fake news.” To make sense of it all, I analyze the impact of my own internal and external processes. I examine my foundational assumptions and interpersonal engagements. And, I do all this self-examination in an effort to understand how my own behaviors affect those in our communities who are marginalized and under-served. What I fail to understand is how I can possibly process human behavior or social condition through a lens that is anything other than distinctly my own. I consistently come up against the realization that my lens is completely egocentric. So how would I undertake an equity lens refraction – an examination of how experiences passing through my uniquely ground lens project distorted images? Especially since I depend on my own unique lens to refract my experiences to draw conclusions and make judgements every day. Puzzling over this dilemma, I remembered an encounter with Howard Zinn that challenged me to entertain “differing versions of reality." In his book, The People’s History of the United States, Zinn argued that American history is to a large extent the exploitation of the majority by an elite minority. This American historian and political scientist relied on a large sample of first-person narratives to present alternate interpretations of the commonly taught version of United States history. Discovering that the Arkansas legislature planned to ban Zinn’s books from its public schools, I realized that I had to understand the unique lens Arkansas legislators used to make that decision before I could understand why they made it. Such an investigation did not imply sympathy to the cause or a tacit agreement with its assertions.

While I have been expanding the perceptual field of what I recognize to be real and true in the world, I cannot deceive myself into thinking that I am standing on some absolute value about things outside myself. I have yet to stumble upon a pure equity lens that exists in some ideal world separate from my real conceptual world. I wonder how close I can get to viewing the world without distortion. And, if each of us continues to refract the world through our individual lenses, I wonder if we can ever come to agree on what a perfectly equitable world looks like. So, in the past 11 months, I have looked through many lenses and have come to appreciate the many different worlds I have glimpsed through the eyes of others. Given the realities of our time, though, the story of “The Emperor’s New Clothes” has taken on new meaning. I now can understand how some citizens might gaze upon the Emperor's flamboyant finery with admiration, while others look upon the procession in confusion and horror that the Emperer isn't really clothed at all. ▀ ▀ ▀ |

|

|

| Poetry |

Remembrances Remembering Margaret Milburn Hands in Joy Forever By Joseph Corrado Her hands have been in many bubbles Liquids and powders and sprays, they say, In buckets and bathtubs and basins and bowls, Now here's a tribute: "A Detergent Award"

Remembering Anna Kessler

My Mother’s Love By Basha Krasnoff When I think of my Mother, I have visceral memories of her holding me, soothing me, and comforting me. I can still remember looking into her eyes and seeing the deep love and appreciation she felt for me. I can still feel her smooth beautiful cheek against mine and hear her comforting voice as she held me close. The pain of missing her remains a subtle ache that ebbs and flows as I notice things that draw my mind back to her. Like the sadness I feel looking out the window into the garden, knowing that these were the last glimpses of the world outside that she ever had. Sometimes, when I look at my son, her only grandchild, I feel as if I can actually see him through her eyes, and for those brief moments she can be present with me, seeing what we each love. When my heart is aching for my Mother, I think about what she always gave me in my moments of need. As a child, I saw in her eyes a reflection of who I am. I understood the truth of who she thought me to be. And, although I came to know myself through her eyes, I realize that it was not until her death that I came to stand on my own and become my own person. Thus, the bittersweet irony of motherhood.

|

|

|

| CONTRIBUTORS |

| Spring 2020 |

|

Mehreen Ahmed Beth Cartino Angie Ebba Mary Ellen Gambutti Michael Lee Johnson Mark Kodama Basha Krasnoff Andréa Montoya Kenneth Pobo Fabrice Poussin Prisoner # 53.3.8.5.7 Shavaun Scott Dawn Tyree |

|

|

| SUBMISSIONS |

| Spring 2020 |

Buoyed by the thriving literary community of Portland, Oregon, we reach out to the global community to inspire, encourage and broadcast creative expression. Wherever you are on planet Earth, we welcome you to share your vision, your voice, and your point of view! The Portland Metrozine is published quarterly (Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter), but submissions are accepted at any time. We accept simultaneous submissions but please let us know if your work is accepted elsewhere. We will consider previously published work with a citation for the original publisher and date. You can learn more about our community via Facebook and Duotrope. Submission GuidelinesSend an email message to the Editor at: 1. In the body of your email, please include: ■ Title of your submission 2. For document files, use MS Word (.doc, or .docx), or ASCII text (.txt). Attach your document and/or image file(s) according to these guidelines:

Creative Non-fiction: 1 essay per submission (max: 4K words) ■ double-spaced manuscript ■ one-inch margins ■ paginated

|

|

|

| KUDOS Gallery |

| Spring 2020 |